A recent editorial in the science journal Nature calls for increased assistance to academics fleeing persecution. In many parts of the world, the editorial notes, “academics and their families can face discrimination, prison, or worse, for speaking out about or studying issues that threaten dominant policies or ideologies.” “They can also be persecuted for their politics, or for belonging to a particular ethnic group.”

A number of organizations exist in the U.S. and abroad to assist threatened academics. Probably the most venerable such group is CARA–the Counsel for Assisting Refugee Academics. Founded in the UK in the 1930s to help scientists in continental Europe fleeing the Nazis, CARA supported some 1,500 academics in those dark years, 16 of whom went on to win Nobel prizes. It currently aids around 200 refugee academics annually. At a CARA event earlier this year, Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, summed up what is at stake: “Defending intellectual freedom is defending the possibility not only of a free academy but of a society willing to learn — and thus a society willing to see itself critically.”

In the United States, two groups that assist endangered academics are Scholars at Risk and the Scholar Rescue Fund. Among other things, these groups protect threatened scholars by bringing them to universities in the United States and support academic freedom in countries throughout the world.

It is interesting that these NGOs are able to circumvent the normal refugee/asylum process for the people they are assisting. Rather than applying for refugee status abroad or seeking asylum in the United States, the academics are offered positions at host universities. They can then travel to the U.S. (or whichever country is hosting) using a regular visa (maybe an H1-B visa or a J visa, for example) and remain in legal status while they work at the university. Of course, once they are here, the scholars could apply for asylum if necessary.

I wonder whether this model–of private organizations bringing refugees into the country using the immigration tools at their disposal–could be applied to other groups who are ill served by our immigration laws: gay and lesbian partners of U.S. citizens, for example, or victims of domestic violence, or others who face persecution but cannot establish that the persecution is “on account of” a protected ground. I know professors are a special category–highly educated and employable under different immigration categories. But perhaps this type of “private political asylum” could be used to help others in need.

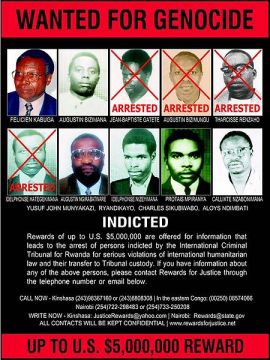

Beatrice Munyenyezi, 40, of Manchester, New Hampshire was indicted last week on two counts of lying to obtain her U.S. citizenship. According to a report from the

Beatrice Munyenyezi, 40, of Manchester, New Hampshire was indicted last week on two counts of lying to obtain her U.S. citizenship. According to a report from the